When Gregg Gillis performs, audiences go wild. So does he. Better known as Girl Talk, he runs around the stage, stripping off his clothes as he moves with the energy of his catchy dance beats. Girl Talk performs at venues as touted as the Coachella music festival in Los Angeles and tours internationally. When he released his most recent album All Day online in 2010, “Girl Talk” was the most searched for phrase on Google for much of the day.

He is a music sensation, but Girl Talk neither sings nor plays an instrument. He plays music off reinforced Toughbook laptops protected from his sweat by layers of plastic wrap. To create an album, he mixes elements of songs from genres like hip-hop, rock, and rap. All Day begins by playing the classic English rock band Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs,” then layering on top of it vocals and percussion from American rapper Ludacris and hip-hop artists JC and Yung Joc. A completed album takes what are known as “samples” (pieces of other songs) from several hundred songs.

In Girl Talk’s view, he is a musician: “I want to be a musician and not just a party D.J., and like any musician I want to put out a classic album.” The music industry, on the other hand, views his unlicensed use of other musicians’ music (which Girl Talk does not pay a dime for) as criminal.

For listeners of Girl Talk, part of the fun is recognizing their favorite songs diced up among or played against other hits. The same is true for his fellow mashup artists like The Hood Internet and Super Mash Brothers. For a casual observer, it may seem reasonable that these mashup artists should pay the copyright holders for using samples of their hit songs. And legal precedent in the US and most of the world says that they should.

Sampling, however, is used to create a majority of the new music we hear today. Producers and DJs create electronic and dance music by sampling old soul, funk, and rock tracks (think of house music playing at a club). Samples are also used to create the instrumentals of nearly every rap and hip-hop song (the background to nearly every rap is sampled), a surprising amount of pop including songs by Carly Rae Jepsen and Christina Aguilera, soundtracks, and even commercial jingles.

Although this all falls under the umbrella of “sampling,” huge variation exists between the uses of samples. Puff Daddy’s hit “I’ll Be Missing You,” for example, was created simply by adding new vocals on top of the instrumentals from The Police’s “Every Breath You Take.” In contrast, an electronic DJ may take several 2 second samples, loop them to fill up a track’s worth of time, and manipulate them digitally until the musicians who first recorded the samples would never recognize them. Mashup artists, by cleverly combining small but recognizable chunks of songs, fall somewhere in between. But the law treats all these instances as identical uses of copyrighted material. Regardless of how the samples are used, producers must obtain permission from the copyright holders or risk a lawsuit.

The result is a broken system that impairs the ability of young producers to make music without taking huge legal risks. The task of obtaining permission to use a sample, even if only a two second sample that will sound nothing like the original, is so difficult and expensive that only big players in the music industry have the resources to pull it off. While the process of making music becomes increasingly digital, artists searching for their big break are unable to play by the rules, putting the future of the industry at risk.

The bad news is that until the legal system recognizes the difference between sampling entire tracks and using short samples as the raw material from which to build something entirely new, every promising producer and DJ is a lawsuit waiting to happen. The good news is that if any of those lawsuits actually sees its day in court, rather than being settled by lawyers before a judge can rule, the system may be fixed. Because copyright law may actually be on the side of Girl Talk and the samplers.

A Symphony of Samples

To create music from samples, producers begin by dragging mp3 files into a digital audio workstation, or, within the workstation, creating sounds with virtual synthesizers and drum machines. They use these clips and sounds to create new music.

With the workstation, producers can manipulate, arrange, and layer the samples. Mashup artists use samples ranging from 10 seconds to an entire song. A hip-hop producer may loop a few bars of drumming as background for a rap. Electronic artists work from samples as short as a few seconds. The possibilities for manipulation are endless. Producers can fiddle with speed, key, and much, much more.

Although it is obvious which songs Girl Talk samples in a mashup, artists often do not recognize samples of their own music. In the UK, one producer sued the dance group MARRS for sampling his work. Although the song was a top ten hit, he had no idea it sampled his song until a member of MARRS mentioned it on the radio. It had been manipulated beyond recognition. With enough work, any sound can be sampled for a song. Entire albums have been made from the audio of pornography videos, but they still sound instrumental.

Producers have two options when working on a laptop. Many create a track and export it into a file as a finished product. But producers can also load the samples they want onto a workstation and then work with them in real time as a live performance. This is what artists like Girl Talk do regularly.

Young producer and DJ Soren Jahan, who likes sampling old movies for the “texture of their sound,” told us he believes there are no criteria that define good samples or sampling technique: “There are as diverse good and bad ways to sample music as there are to make music. In the digital world, you can take any sample and turn it into anything. The problem, if anything, is being paralyzed by too much choice.”

The Amen Break

The story of how sampling became industry standard for musicians and producers is best told through the story of “the Amen Break.” Four bars of music that became widely sampled, it is, in the words of an Economist article, “a short burst of drumming [that] changed the face of music.”

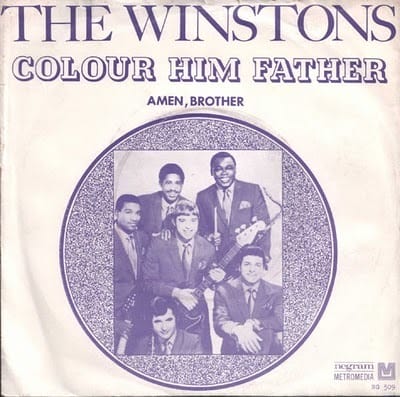

The clip comes from the song “Amen, Brother” by The Winstons, a soul band. The group won a Grammy in 1970 for their song “Color Him Father,” but today they are known (if not by name) for a short drum solo in “Amen, Brother,” the rushed, unremarkable B-side to “Color Him Father.”

In the 1980s, people had ceased listening to The Winstons. However, the development of cheap and easy to use samplers allowed old music to live again in new forms. Samplers were hardware that enabled users to record any sound into it and then play it back and manipulate it. Drum beats and guitar riffs from various songs could be combined with original recording.

Samplers, along with turntables, enabled the hip-hop scene. In 1986, a collection of “clean, drums-only segments” made for hip-hop production included the Amen Break. The sample became one of many used in the burgeoning hip-hop world. For the most part, producers looped percussion samples to form a background for rapping.

In the 1990s, the British dance-music scene discovered the Amen Break. Adding to a hip-hop trend, they manipulated the drums to be a central part of the track in what became known as jungle music, and rave audiences began to recognize and crave its mutations. Rather than making simple changes to the break and looping it, producers manipulated it nearly beyond recognition. The editing became the art form: “For a time anyone trying to build a name in the scene had to turn their hand to Amen.”

Even after jungle’s demise, the Amen Break enjoyed a long afterlife. A “highbrow crowd” continued to enjoy manipulations of the Amen Break like a fine wine, but as sampling and electronic music progressively made inroads into the mainstream, new producers sampled it to reference the past or try their hand at a classic. Several companies released it as a sample for the production of commercial jingles. The animated show “Futurama” by Matt Groening, creator of “The Simpsons,” uses it for its theme song.

Although the Amen Break may be the most sampled track ever, used in hit music and commercials, The Winstons did not earn a dime for its use. The drummer died in poverty in 2006. The lead singer, Richard L. Spencer, calls it “plagiarism” and “bullshit.” He told The Economist, “Guys copy and paste it and make millions.”

The Lawyers Arrive

When kids in New York City began rapping to looped samples of other musicians’ music, no one cared. Hip-hop was not seen as having appeal beyond a small, underground, and unprofitable niche. But when hip-hop and sampling joined the profitable mainstream in the eighties and nineties, corporations took notice and sought to apply copyrights.

It was not inevitable that sampling would be labelled copyright infringement. Artists drawing from famous works of art to create collages are not sued. Author David Shields’s recent novel Reality Hunger, which cuts and pastes other authors’ words the way Girl Talk does guitar riffs, received accolades from critics without a peep about copyright or plagiarism.

Two court cases are credited with equating sampling and copyright infringement in the American music industry.

The 1991 case Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records Inc. concerned rapper Biz Markie and the singer/songwriter Gilbert O’Sullivan whose work he sampled. The judge began his opinion like God unleashing biblical floods with the words “Thou shalt not steal.” He found in favor of Gilbert O’Sullivan and even referred Biz Markie and his record company to the US Attorney for criminal prosecution.

The judge did not consider the idea of fair use, the doctrine that dictates permissible exceptions to copyrights. As a result, major record labels began publishing only albums that had cleared all their samples. Kembrew McLeod, co-author of Creative License: The Law and Culture of Digital Sampling, marks this case as the end of “the golden age of sampling.”

A 2005 case, Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films, cemented the norm of needing to clear the use of any sample. Overturning the ruling of a federal judge, the US Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit ruled that the defendant’s sampling of a two-second guitar chord constituted copyright infringement.

Clearing a Sample

Unfortunately for anyone who does not enjoy endless series of phone calls and steep legal fees, getting permission to use a sample (“clear” it) is an expensive pain in the ass.

For each sample you want to clear, you need to track down “two different rights-holders: whoever owns the sound recording (the actual sound that’s been fixed to magnetic tape, CD, etc.) and the song publisher (who owns rights to the underlying melody and lyrics).” But there is no standard way to find the rights owner. The copyright owners may or may not be written on the CD (or labelled digitally), and since copyrights can be sold, the holder may not be the original artist and record label. Since most recording copyrights are held by giant record companies, anyone other than an industry star or music professionals can struggle to track down someone with decision-making ability on the copyright.

But finding the copyright owner is no guarantee of success in clearing the sample. You still need to negotiate:

“There is no standard guideline or fee structure for sample usage, and some copyright owners find it not worth their time to deal with requests that will not net a significant income stream. When they do agree to work with you, the rates may seem prohibitively high if you yourself do not have a large-grossing project on the table and a major label (and that label’s lawyers) behind you. A sample deemed ‘very central’ to a secondary project could be met with a request for a 50:50 profit split…”

Due to the legal precedents empowering copyright owners, as well as the power disparity between giant labels and small-time artists, a music producer that seeks to play by the rules could be asked to share writing credit and split profits 50-50. Or the copyright holder may not even bother with anyone not grossing millions in sales.

Clearing samples is not impossible. The music industry is full of examples of basslines and melodies being used over and over. It is hard for unestablished musicians to do, but when it comes to using large, recognizable samples of popular songs, that does not seem unreasonable.

However, clearing samples has become increasingly difficult over the past two decades. It can be prohibitive even for major stars, and the costs render the use of many samples impossible today. The Beastie Boys’ 1989 album Paul’s Boutique averages around 7 samples a song from artists including Led Zeppelin and Paul McCartney. If they produced and released the album today, and it again sold 2.5 million units, the record company would lose roughly 20 million dollars due to the cost of clearing all the samples.

Since all samples are treated equally, producers who sample in the style of the Beastie Boys – by densely layering many samples – can no longer do so legally. For producers who go even farther and use two second samples manipulated beyond recognition, this seems particularly unfair.

Girl Talk’s album Feed the Animals, which uses over 300 samples, would have never been made if he felt the need to do it legally:

“It would take you hundreds of hours of work and hundreds of thousands of dollars to clear the rights to this album even if you wanted to.”

The current legal state of paying for every sample also means that it is effectively impossible to sample a song from bands like the Beastie Boys or Girl Talk because doing so would require clearing not only the samples of their songs, but also the samples that they used. If artists continue to sample heavily in the future, the price of clearing samples could literally increase exponentially.

Making Music in Legal Purgatory

Although major record labels refuse to release albums with uncleared samples, the same is not true of smaller fish in the music industry. We talked with Soren Jahan, a producer/DJ of electronic and dance music and co-founder of two record labels, Blank Slate and Supply Records, to understand the impact of sampling’s legal situation on producers like him. He is young, relatively new, and just one facet of the music industry, but in a position similar to thousands of artists looking for their break.

When asked about the legal situation, Soren responded “we don’t hear the word royalties very often.” Sites like Freesound offer pre-licensed samples for producers to use with a simple citation, but producers rarely distinguish between licensed and unlicensed samples. Soren explains, “It’s pretty much the Wild West. When you can drag any mp3 into the software, there is no particular trend.”

Soren says that producers and small record labels decide whether to risk publishing works that use unlicensed samples based on four criteria – the length of the sample, the fame of the band, the extent to which the sample is modified, and the size of the audience and expected profit.

These are not standard criteria; they are simply the factors that inform people’s thinking about the risk of getting sued. It is easier to use an unlicensed sample if it is a small clip from an obscure band and manipulated until even the musician that produced it would not recognize it. Labels with tiny (or nonexistent) profits or a very niche audience also face less risk – suing them is unprofitable.

But as producers make music with unlicensed samples and labels distribute them without due diligence, no one can be sure when they will cross a red line and face a lawsuit. And, of course, if an unknown producer does create a hit, record companies could then sue him or her for millions.

As to whether club owners ever enforce copyright on their DJs, “I have never in my entire life heard of that type of thing happening in the US,” Soren said. “It’s understood that the majority of people who play music digitally download music from blogs. There’s a kind of don’t ask, don’t tell policy.”

But that understanding is tenuous. New rules in Germany, Soren told us, have begun requiring clubs to scan the computers and hard drives of DJs and charge for the mp3s they find. He’s heard crazy numbers thrown around about money owed for illegal downloads similar to when the first users of Napster were fined tens of thousands of dollars. “It’s hard,” says Soren, who will move to Germany to DJ more this summer, “But I understand that artists need to get their fair shake.”

What Pirates?

While the universality of clearing samples among major record companies seems to indicate respect for established legal rulings, the question of whether unlicensed sampling constitutes theft is not settled. The defenses offered by artists like Girl Talk for why their sampling does not break copyright law have never been tested in court.

The purpose of copyright law is to grant the creator of something original – whether a medicine, product, or sonate – a fixed period of monopoly over their invention in order to profit from it. This serves to incentivize innovation and creativity. The American Constitution laid the foundation in the US through the Copyright Clause, which reads:

“To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

Its purpose, according to James Madison, was “to encourage, by proper premiums & Provisions, the advancement of useful knowledge and discoveries.”

This philosophy – that copyright should incentivize private creativity without stifling public innovation – has informed changes to copyright law in the United States and throughout the world. It is applied internationally in the Berne Convention, which is now part of the World Trade Organization.

Given the purpose of copyright law, producers and DJs like Girl Talk can make a compelling case for why sampling does not break copyright law.

In America, the 1976 Copyright Act defines the circumstances under which exceptions to copyright law are permissible as “fair use.” Section 107 lists potential exceptions of using copyrighted material as “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research.” This doesn’t include music producers working with samples, but the criteria defining fair use, which the act admits is not easily defined, are as follows:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes

- The nature of the copyrighted work

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work

One of the reasons small record labels are able to distribute songs that use unlicensed samples is because they are no longer recognizable. It is like suing a painter for copying your landscape painting – if the other painter had a copy of your piece, took the paint from the upper-right corner, and painted an entire cityscape with it. This suggests fair use under the third criteria.

Nor can the new use be said to prevent the copyright holder from profiting from his creation – the explicit purpose of copyright law. This is true even of Girl Talk. No one stops listening to ACDC because they can listen to one ACDC guitar riff on a Girl Talk album.

The actual violators of copyright law may be the big fish of the music industry and their lawyers who benefit from the misguided rulings of two out of touch judges and perpetuate a misapplication of copyright philosophy. In the words of Kembrew McLeod, co-author of Creative License:

“There’s no reason why a court, judge, or jury couldn’t consider an audio sample transformative use. But no sampling lawsuit in which the defendant has argued for fair use has ever reached a decision stage. In every instance, the defendant has settled out of court—because the case would probably go all the way to the Supreme Court, and it would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to get to a decision.”

Law professor Peter Friedman concurs. Imagining himself advising someone holding the copyright to a song sampled by Girl Talk, he says:

“I would advise that client not to sue Girl Talk; Gillis’s argument that he has transformed the copyrighted materials sufficiently that his work constitutes non-inringing fair use is just too good. I’d go after someone I am more likely to beat. Othewise, I’d lose all the leverage I have with the existence, as yet undisputed in case law, of the decisions in Grand Upright Music and Bridgeport Music.”

For major record companies, charging producers for using samples is effectively free money. Although they have to pay to clear samples for their clients from time to time, they can reap profits by sending their lawyers to collect from many others. Small time artists lack the money and lawyers to keep appealing the rulings, and getting a ruling would delay the release of a track or album so long that it is not worth it.

So why hasn’t Girl Talk, aka Mr. Gillis, been sued despite infringing on the copyright of nearly every major record label? Well, the “screw you” attitude taken by him and other mashup artists suggests they may be willing to see a legal challenge to its end no matter how many lawyers record companies send at them. And the law may be on their side.

Solving the Sampling Dilemma

At Priceonomics, we don’t have any insight into the trends of the music industry. But our amateur instincts tell us that the infiltration of electronic music into all forms of popular music won’t stop anytime soon. And that means that sampling will continue to play a role in music creation for years to come.

The current legal system around sampling is outdated and broken. It was created in 1991 by a judge throwing Bible quotes around who (more importantly) failed to consider the doctrine of fair use. Treating all samples the same unfairly burdens producers who use samples to create unique and original work. They system has been maintained by the economics of how it benefits players in the industry with the most time, money, and lawyers. The claims of producers like Girl Talk – that sampling constitutes fair use and is in line with copyright law – should see its day in court.

Until it does, the music industry will continue to be hampered by ambiguity that stifles creativity. Clearing samples can be impossible for all but the biggest stars, which leaves the music industry’s dreamers facing a hard choice between restricting their creativity or making music with the nagging fear of a lawsuit. A law that makes it impossible to play by the rules is not a good one.

The system of clearing samples is inefficient and unpredictable. Wikipedia has a good summary here of various lawsuits around uncleared samples. Some cases, like MC Hammer’s sampling of Rick James’s “Superfreak,” have resulted in settlements that allowed both to profit. Others have not. Courts can order all copies of albums destroyed and ruin careers. After The Verve made the mistake of sampling from a cover of the Rolling Stones (an infamously protected copyright) in their hit “Bittersweet Symphony,” a judge ordered them to return 100% of their profits. The band did not survive the blow.

There are potential improvements that could be made to the system. If more artists release their work under licenses like Creative Commons, which allows creative uses of copyrighted work such as sampling, then producers would not be as constrained.

Another possible solution to decrease the inefficiency of the sampling ecosystem would be to legislate a fixed rate for the sampling of music. In this way, artists would still be compensated if someone samples their music, but it would be automatic, predictable, and (hopefully) affordable.

But there is another solution. If the music industry feels confident enough about the legality of samples to sue producers as criminals, then they should sack up, sue Girl Talk, and settle the matter once and for all. Until then, the music industry will remain in a legal gray area just as threatening to its future as music piracy. And Girl Talk will continue cutting up everyone’s music, raging to it, and daring someone to sue him.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. Thanks to Soren Jahan for sharing his perspective. Good luck DJing in Germany!

Correction: This post previously wrote in error that Freesound offers unlicensed samples. The site actually offers samples with licenses that allow them to be used with a citation.