A bottle of Château Lafite Rothschild Bordeaux is considered by many to be the world’s greatest wine. In the 17th century, both the British Prime Minister and King Louis XV drank it regularly. In 1855, when Napoleon instructed French wine experts to classify France’s Bordeaux wines, Lafite Rothschild earned a top spot as a Premier Cru, a rank it maintains to this day.

Thomas Jefferson ranked among its admirers. In 1985, a 1787 bottle of Lafite Bordeaux that he supposedly owned sold at auction for $156,000. It was the most expensive bottle of wine ever sold. Chateau Lafite Rothschild released their most recent Bordeaux for 420 euros a bottle. Older bottles command prices higher than $1,000.

Wine experts discuss Lafite as if they are tasting an ever-changing Impressionist painting. “The wine still has a dark ruby/purple color and an extraordinarily youthful nose of graphite, black currants, sweet, unsmoked cigar tobacco, and flowers,” writes influential American wine critic Robert Parker on the 2000 Lafite. “I originally predicted that it would first reach maturity in 2011, but I would push that back by 5-7 years now.”

However, it’s unclear whether anyone can tell the difference between a $2,000 Lafite Bordeaux and a $3 table wine. In fact, most wine economists consider the matter settled. Blind tastings and academic studies robustly show that neither amateur consumers nor expert judges can consistently differentiate between fine wines and cheap wines, nor identify the flavors within them.

So, what’s going on in the wine industry? If a $10, $100, and $1,000 bottle all roughly taste the same in a blind taste test, how do you explain their different price tags?

How the World Produces 23 Billion Liters of Wine

Wine is simply fermented grape juice, but its production is a finicky process. Very real differences in production exist between top and bottom-shelf wines.

Asked about the keys to winemaking, the proprietor of Domaine Dujac, an expensive French Burgundy wine, responded, “The soil, the soil, and the soil.” In fertile soil, grapes fill with water that dilutes the flavor. Only grapes grown on rocky or otherwise challenging land stay flavorful. Characteristics of the soil also impact taste, as do the climate and topography. The French use the term “terroir” to express how these characteristics flavor wine.

It’s easy to get lost in the complexities of winemaking. But looking at the two poles of the wine market – a two dollar Charles Shaw chardonnay and a pricey Lafite Bordeaux – aptly demonstrates differences in production.

Charles Shaw wine is nicknamed “Two-Buck Chuck” because it first sold at Trader Joe’s supermarkets for $1.99. The makers, the Bronco Wine Company, grow grapes in California’s Central Valley. The soil is considered too fertile to produce flavorful grapes, but produces high yields.

The process is an economy of scale par excellence. Once picked, grapes are processed and bottled in “a high-speed bottling plant capable of churning out 18 million cases of wine a year, double the annual production of all the rest of Napa Valley.” Bronco also buys surplus wine from other California vineyards at bargain prices.

Owner Frank Franzia doesn’t bother with notions of terroir. All the wine is blended together, regardless of its origin. As of 2003, Bronco processed 300,000 tons of grapes to make 20 million cases of wine, of which a quarter are Charles Shaw wines. Asked how he sells wine for the same price as a bottle of water, Franzia responded, ““They’re overcharging for the water. Don’t you get it?”

Lafite treats viniculture as art. Its soil of gravel, sand, and limestone in the Medoc region of France results in low yields but flavorful grapes. Various combinations of grapes are tried in pursuit of the best possible vintage. Only grapes grown in the chateau’s best soil are bottled as premier cru (first growth) Bordeaux. The rest are bottled as a “second growth” that sells for a fraction of the price. Total production is under 100,000 cases a year. On-site coopers make wooden barrels specially suited to imparting flavor. Staff light candles in the tasting area before wine is sampled. Although not every wine benefits from extensive aging, Lafite Bordeaux ages for a decade or more before maturing into complex flavors.

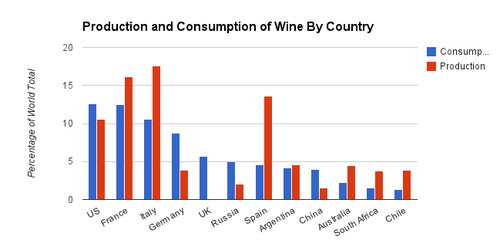

But not every wine is produced and sold by wineries. Wine merchants called negociants buy wine to bottle and sell under their own name and label. Every year, wineries make more wine than they can sell. The world consumed only 23.21 billion liters of wine in 2010. Wineries produced 26.38 billion liters. Negociants buy and sell this surplus.

Savvy salesmen can make good money. Cameron Hughes, an American negociant, sells 400,000 cases of wine at prices ranging from $10 to $60. Giant labels like Charles Shaw and Yellow Tail, despite having their own vineyards, mostly buy and blend other wineries’ grapes.

For some wineries, selling to negociants is a shameful necessity. Other wineries, especially smaller ones focused on the winemaking process, are happy to have someone do the sales work that they prefer to avoid.

Just four countries, Italy, France, the US, and Spain, produce 58% of the world’s wine; they also consume 40% of it. But the market for fine wines is more globalized. Chateau Lafite Rothschild exported 75% of its premier cru in 2008.

Pricing Wine

To learn more about the wine industry, we talked with Troy Carter, founder of Motorcycle Wineries in San Francisco. He explained wine as having two industries: one is industrial, efficient, and cheap; the other is romantic and expensive.

Cheap and efficient wine constitutes the majority of wine that the world drinks. Among Americans who drink wine regularly, only 12% spend $30 or more on a bottle weekly or monthly. Yellow Tail, a budget Australian wine, is the number one imported wine in America. The US imports more Yellow Tail each year than the total number of bottles imported from France. Troy estimates that 90% of wine by volume is under $10 a bottle.

In this part of the market, price is mostly determined by production and distribution costs.

Wine is widely dispersed to stores, supermarkets, restaurants, and private collectors. Wineries avoid these sales responsibilities, so wine merchants and distributors do the work for them.

Troy Carter describes the distribution process – for a wine that sells for about $30 – as follows. Distributors buy cases of wine from the maker at $15 per bottle. They then sell it to restaurants and stores for $20. Restaurants’ markups vary, but stores consistently sell it for $29. Vacationers in Napa Valley will pay $30 to buy the bottle directly from the winery – it is something of a standard that bottles cost one dollar less at stores than at wineries, according to Troy. Supermarket chains like Costco, which is the largest provider of wine in the US, sell the bottle for around $22 – just above wholesale prices.

For cheaper wines, the economics of distribution work similarly. When you buy a $6 bottle of Yellow Tail chardonnay, that somehow covers the production cost, taxes, import duties, and various markups.

The boundaries are fuzzy, but as you look at the pricing of mid-range wines that cost from $10 to $70, the rules are less straightforward. Marginal production costs become disentangled from price. At $50, Troy told us, pricing is nearly independent of production costs.

In this range, brands can dramatically affect price. The same wine in two differently branded bottles can have very different costs, as shown by the prices offered by negociants such as Cameron Hughes:

“Hughes signs confidentiality agreements that preserve a winery’s anonymity. After all, a producer of a $40 Napa Valley cabernet sauvignon doesn’t want his customers to know they can get a nearly identical wine from Hughes for $25. Yet the winery might need to move out surplus inventory, generate cash flow or make full use of capacity, a win-win-win situation for the producers, consumers and Hughes.”

The region of origin also significantly impacts price. Wines from Napa, for example, are 61% more expensive than other Californian wines, everything else being equal. This reflects differences in quality, as Napa’s soil and many of its winemakers are well regarded. It also speaks to the branding power of certain regions. There is a reason that Napa winemakers cry foul when Frank Franzia labels Charles Shaw as Napa wine, even though the grapes come from the Central Valley.

Reviews by prominent wine critics also impact the price of a bottle of wine. The reviews of Robert Parker, the world’s most influential wine critic, can dramatically impact price and demand. (He is known for fine wine, but tastes wines as inexpensive as $20.) As a definitive Atlantic article said about Parker:

“A positive review and a score over 90, especially for a wine that is produced in small quantities, can ignite speculation that sends the price rocketing and clears the wine out of the stores.”

A mix of production and distribution costs, brand reputation, pricing strategies, and quality and critical reception determine prices of mid-range wines. There are some pricing anomalies, but for the most part, the market for wines in the $4 to $70 range operate how you’d expect markets to work.

Fine wines, however, are a different beast. Almost entirely cachet, their prices rise and fall with little connection to quality.

Speculating In Human Snobbery

One night in 2007, this author found himself at a dinner party at a billionaire’s house. After the meal, the host gave a tour of his wine cellar. “The best part of having a wine cellar,” he confided, “is that you can drink thousands of dollars of wine for free.”

He accomplished this by taking advantage of the fact that many wines increase in quality, and therefore in price, as they age. Until the turn of the millenium, oenophiles wealthy enough to sit on thousand dollar cases of wine for a decade dabbled in “investing” in wine, usually with a glass of Bordeaux in hand. As described by commentator Darius Sanai:

“For centuries, investing in wine was fairly straightforward. You would buy as many cases of classed-growth claret en primeur (as futures) as your budget allowed, watch their value double over the next few years, take delivery of half of them, and sell the remainder to recoup your initial investment. Your capital was returned to you, and your interest was carried in all the fine wine you would need to entertain your guests over a lifetime.”

And if an investment went bad, you simply threw a very expensive dinner party.

In the mid 2000s, Chinese nouveau riche entered the fine wine market. China’s economic growth produced over one million millionaires who sought out Western status symbols. London filled with third-world businessmen who drove Maseratis and shopped at Harrods. New York City received the same treatment, as did luxury brands like Gucci. And fine wine.

The demand for premium wine skyrocketed. Prices saw exponential growth from 2008-2010. The below graph shows the value of fifty premium wines over time, accounting for the increased price of aged wines:

Whereas premium wines once only modestly appreciated in price, suddenly ten thousand dollar cases doubled in price in a year. Hong Kong auctions of Chateau Lafite Rothschild commanded prices at double their traded rates in the United States and Europe days earlier.

Financiers took note. Banks set up fine wine divisions and wine investment funds began shopping for clients. An organization called the London International Vintners Exchange (Liv Ex) created indices for fine wine. The Live Ex 50, which charts the prices of the world’s top performing 50 wines, acts exactly like the Nasdaq 500 does for stock brokers. Investors can buy what essentially amount to futures by buying wine “en primeur” before it is bottled.

To understand the economics of fine wine, we talked with James Maskell, who created Vinetrade, an online marketplace for wines.

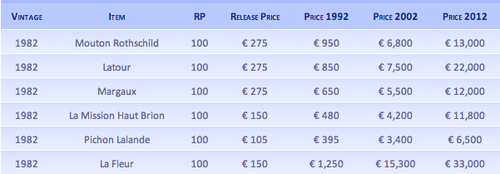

According to James, the Chinese preference for these elite wines is mostly about cachet. Bottles are being purchased as a symbol of wealth – or to use as a bribe. According to James, the “pricing is maybe 25-30% quality, 70-75% brand.” Since cachet is all about rarity, demand for a wine (say, a 1982 Mouton Rothschild Bordeaux) increases as supply decreases, accelerating the appreciation of wine prices.

This market consists of very few wines. According to Liv Ex:

“The top 25 chateaux in Bordeaux and a handful of properties from other regions dominate. Indeed, our research suggests that just eight wines – the five First Growths, plus Petrus, Cheval Blanc and Ausone – account for more than 80 per cent of a typical wine fund’s portfolio by value.”

But investors cannot simply buy top wines and wait for them to appreciate in value. In 2008, Bordeaux producers raised their prices dramatically to capture the profit margins made by speculators. Merchants and investors balked, and suddenly the bubble popped. Investors undercut each other in their hurry to sell. Cases priced at £15,000 sold for £6,000 or £7,000 before the market stabilized.

The top Bordeaux alone cannot satisfy demand, so today’s wine investors need to predict the next wine to be anointed a member of this market. Bordeaux second wines took off first, then elite French Burgundies. One investor James knows buys similar Italian wines in the expectation that they too will become an elite wine.

So today, wine analysts in London, New York, and Hong Kong assemble “huge spreadsheets with things like critic scores, drinking windows, available supply and prices that they manually compile and analyse” in search of the next wine that Chinese businessmen will buy to one up each other. They speculate in human snobbery.

The supply of “great” wine is decreasing, because inevitably, someone drinks a bottle. At the same time, the demand is skyrocketing. But is the demand for expensive wine remotely rationale? Can our brains tell the difference between the taste of an expensive wine and cheap wine?

Is Wine a Hoax?

The academic literature on the taste and quality of different wines is robust and damning: when tasting wines without reference to their name, type, or price, no one can consistently identify them or rate their quality.

In 2007, Charles Shaw was named California’s best chardonnay at the California State Fair Commercial Wine Competition. “It was a delight to taste,” announced one judge. In 2012, top French wines (including the premier cru Château Mouton Rothschild) barely defeated wines from New Jersey in a professional tasting. The Jersey wines cost 5% as much as the French wines.

These results are not aberrations. A 2008 paper in The Journal of Wine Economics found that when consumers are unaware of a wine’s price, they “on average enjoy more expensive wines slightly less [than cheap ones].” Experts do not fare much better. The study could not conclude that experts preferred nicer wine: “In sum, we find a non-negative relationship between price and overall rating for experts. Due to the poor statistical significance of the price coefficient for experts, it remains an open question whether this coefficient is in fact positive.” Further academic evidence strongly suggests that experts cannot identify “good” wine.

The 100 point scale for rating wine, invented by Robert M. Parker Jr., is extremely influential. According to the buying director of prestigious wine merchant BB&R, “Nobody sells wine like Robert Parker. If he turns around and says 2012 is the worst vintage I’ve tasted, nobody will buy it, but if he says it’s the best, everybody will.”

When retired statistician and hobbyist winemaker Robert Hodgson successfully lobbied to measure the accuracy of the system, his results showed that the judging was completely inconsistent. By having the judges rate the same wine multiple times, he found that:

“The judges’ wine ratings typically varied by ±4 points on a standard ratings scale running from 80 to 100. A wine rated 91 on one tasting would often be rated an 87 or 95 on the next. Some of the judges did much worse, and only about one in 10 regularly rated the same wine within a range of ±2 points.”

Year after year, Hodgson replicated his results. When he broadened his scope to results of hundreds of wine competitions, he found that the distribution of medals “mirrors what might be expected should a gold medal be awarded by chance alone.”

More sanguine critics – who do not dismiss studies like Hodgson’s as “hogwash” – often point to the shortcomings of tastings and the subjectivity of taste. But a number of experiments show that experts’ descriptions of wine’s flavors are equally flawed.

In one experiment, critics tasted one red wine and one white wine. They described the red in language typical of reds and the white in language typical of whites. The problem? Both were identical white wines; the “red” had been tinted with food coloring.

Why then do critics and consumers believe that there are superior wines that justify a higher price tag? Well, outside the world of double-blind taste tests, perceptions matter. People are influenced by wine critics, marketing, and fear of not understanding the rules of the wine game.

Numerous experiments have shown that people will enjoy a table wine and a fine wine equally if they believe that they are both fine wine. Knowing that a wine is supposed to be good does literally make it taste better. The drinkers could be lying about enjoying the “bad” wine due to social pressure. However, an experiment involving a Stanford wine tasting group, a lineup of identical wines presented under fake price tags from $5 to $90, and a fMRI machine measuring activity in areas of the brain correlated with pleasure suggests otherwise. Drinking the same wine with a higher price tag did increase pleasure.

This author has happily spent extra money on wine that he considers superior. But to the best of his knowledge, no compelling account exists to explain away these results. The literature seems clear. Despite the substantial differences in wine production and hundreds of years of history, the only significant difference between wines’ quality is pure perception.

A Tale of Two Startups

In an industry with such inefficiencies, there must be money to be made by clear thinking entrepreneurs, right?

After a year observing wine collectors and investors while working in the industry in London, James Maskell believed that the industry’s opaque network of luddite middlemen offered an opportunity. With venture capital backing, he and a co-founder launched a website called Vinetrade as a marketplace for buying and selling fine wines in 2012. Users could list their wines for sale and buy from other investors and collectors with a few clicks. They aimed to play a “classic intermediation game – connect buyers and sellers, increase transparency, cut margins, and take a small cut” for themselves.

Customers wanted to avoid middlemen’s fees (around 15%) and to buy and sell without picking up a phone, so many people in the market expected them to do well. However, in early 2013, James made the hard decision to shut Vinetrade down.

The most fundamental problem, as they discovered, was that people resisted ordering wine online. For hobbyists, it destroyed the fun of being part of an elite group that unashamedly used words like “tannin” and “subtle.” For investors, it denied them the opportunity to exchange information with salesmen.

“Even if they don’t admit it,” James told us, “people like having the posh voice on the other end of the line. They want reassurance and they want to feel part of the ‘boy’s club.’”

In the stock market, most assets have an underlying value based on objective facts. In wine, taste and quality is a factor of perception. Investors deal, then, in perceptions of perceptions. In the small world of insanely expensive wine, value and prices are determined by what the wine clique is saying about a given vintage.

At best, James estimates that quality is a 25% factor in a fine wine’s price. Sellers could not afford to trade conversations with salesmen for the efficiency of a computer screen because the only currency in the market is everyone else’s take on given wines. It would be like trying to predict the next “it” couple in high school without talking to the popular crowd.

“I think that we proved that people buying wine don’t care about our data and don’t care about our graphs,” James reflected. “They care about what people are saying.”

Meanwhile, In 2012, Troy Carter took a different approach to a wine startup – he bought a motorcycle and began driving around California wine country. He rode up to small wineries, said, “Hi, I’m Troy,” and asked to sample their wines. When he found a wine tasty and unique and the winemaker pleasant and “authentic,” he offered to buy wine to distribute and sell through his mailing list “Motorcycle Wineries.” Trucks drive the wine he buys from California wineries to his San Francisco warehouse where he distributes them to restaurants and individuals.

Troy’s goal with Motorcycle Wineries – beside being able to travel and taste any wine he wants – is to bring romance and authenticity to the experience of buying wine. “If you just want wine that tastes good, you can go to Costco,” he told us. “But there is a large group of people that want to have a unique experience. They want to discover wine at a tasting or at a winery off the beaten path. They want the history of finding something that was sitting in a cellar for a long time. That is what I provide.”

He works only with tiny vineyards where the makers handle the bottles themselves, use natural winemaking techniques like organic grapes, and follow traditional techniques like hand-bottling. High labor costs renders these wines more expensive. “Authenticity does not scale very well,” Troy says. Nevertheless, his bottles cost around $15.

How did Troy convince winemakers to trust him as he got started? By wearing leather. “They’re the only clothes I own,” Troy said, looking down at his understated leather pants and jacket. By showing up on a motorcycle wearing leather, he looked the part of a man who travels the world looking for unique wines. When he didn’t wear leather, he was not taken seriously. “Winemakers ride motorcycles,” Troy told us. “I don’t know why, but they do. Maybe because they have a romanticized vision of wine. Like I do.”

Romancing the Wine Industry

People inside and outside the wine world can argue whether a 1982 Lafite Rothschild is incredible or a scam. But it almost no longer matters. The end result of the fine wine market’s cherished romanticization of wines like Lafite is that now only corrupt businessmen and oligarchs can afford it.

Vinetrade may have failed to bring transparency to fine wine, but Motorcycle Wineries could be just as disruptive. By building a brand that brings magic to $15 bottles of wine, Troy could disentangle the romantic, experience-based aspect of wine that people love from the cachet of premium brands and obscene price tags – with the side effect of offering the same dignity to small, passionate wineries that is currently afforded only to industrial scale wineries with old-timey marketing.

But you, as a consumer, don’t need anyone in the wine business to tell you what to drink. The industry thrives on people’s anxiety about buying good wine, but critics aren’t very good at identifying it. Feel free to buy a cheap wine from the bottom-shelf of the supermarket, and don’t let anyone tell you that you shouldn’t enjoy it. You’ll be just as happy with it.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. He’d like to thank James and Troy for their time, patience, and expertise. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus.