College sports are an $8 billion industry. Without even accounting for the revenues that private companies like CBS and ESPN make from college sports, that is roughly the value of the National Football League.

Given that college athletes are considered “amateurs” for whom sports are an extracurricular activity, the scale of college athletics is incredible. The University of Michigan football stadium, known as “The Big House,” seats over 100,000, making it the 3rd largest stadium in the world. Over 80 million fans watch March Madness, the Division I college basketball championship tournament. In 2010, CBS and Turner Broadcasting signed a $10.8 billion, 14 year deal for broadcasting rights to the tournament.

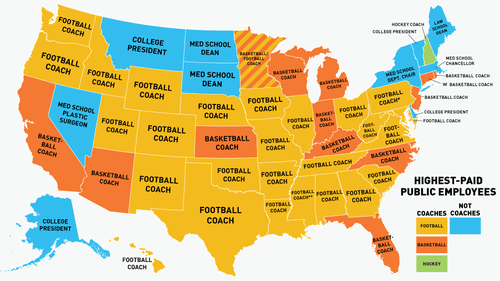

This has made college coaches the best compensated public employees in America. It has turned athletic directors and administrators into high-powered executives that earn six or seven figure salaries and sign million dollar contracts with corporate America. Everyone seems to be enjoying record paydays from the popularity of college sports – everyone but the players, who lose their eligibility if they profit so much as a cent off their status as stars in a billion dollar industry.

Addressing the presence of millions of dollars of corporate money in college athletics, National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) vice president Wallace I. Renfro attempted to clarify his association’s position:

“To be clear, student-athletes are amateurs; intercollegiate athletics is not. The enterprise itself may not be professional, but those employed to administer and coach clearly are.”

The explanation seems simple enough. Just as an accomplished pianist or talented professor will be hired as a professional to work with amateur musicians, the coaches and administrators of college athletics are professional hires and paid accordingly. If corporate sponsors are a necessary component to the management of a large, national athletic association, then they too have their place. They are just the college version of the local ice cream parlor sponsoring jerseys for little league teams.

In 2001, a former university president asked Sonny Vaccaro, a man who made millions by pioneering shoe contracts for brands like Nike and Adidas, whether college athletes should be an “advertising medium for [Vaccaro’s] industry.” He responded cheerfully:

“They shouldn’t, sir. You sold your souls, and you’re going to continue selling them. You can be very moral and righteous in asking me that question, sir, but there’s not one of you in this room that’s going to turn down any of our money. You’re going to take it. I can only offer it.”

The existence of well-funded athletic departments that sell tickets, purvey merchandise, and sign multi-million dollar media deals is unique to the United States. College athletes in the rest of the world operate mostly on a club model. Athletes raise funds themselves to pay for competitions, equipment, and travel.

Are universities taking advantage of student-athletes? Or are they merely running a largescale, amateur pursuit with hard nosed business strategy?

The answer seems to lie somewhere in between.

The marriage of commercialized sports and academic institutions has turned the situation of a small but high profile group of elite athletes into one resembling exploited workers as much as talented student-athletes. But the image of profitable sports teams subsidizing the entire athletic departments or making money for the university is a myth. The sports professionals managing elite college athletics are prospering, but universities are bleeding cash. As college athletics becomes a bigger and bigger industry with ever larger stakes, colleges risk sacrificing huge amounts of funding as well as their academic culture in the race to keep up.

The 1% of College Sports

College sports are an $8 billion industry, but 1% of college athletes are responsible for 99% of the revenue. All this money, commercialization, and national exposure applies to only a very small number of college athletes.

The majority of student-athletes play in Division III, the largest and least competitive of the divisions in the NCAA, which does not offer athletic scholarships or pursue revenue. Many more play in lower divisions (that are not part of the NCAA) or in club sports. In Division II, only a handful of games are televised nationally. Some money exchanges hands between fans, colleges, and private companies, but it is limited.

Within Division I, the majority of revenues are in football and men’s basketball. Texas, the top national football program in terms of revenue, made $103.8 million in revenue in 2011-2012. Ten teams had revenues above $50 million. The Louisville basketball team brought in over $40 million in revenue, with the next most profitable teams earning well over $10 million. In contrast, only two hockey teams had revenues above $5 million and only 4 women’s basketball teams had revenues above $4 million.

Even the elite, big-money sport divisions are sharply divided in terms of commercial size. In Division 1A football, the biggest programs generate 14 times as much revenue as smaller teams. Among the conferences, the most successful (the Big Ten Conference) distributes over $150 million to its members while the tiny Sun Belt Conference splits just over $1 million.

In the most lucrative sports – Division I football and men’s basketball – every player receives a full scholarship. Other Division I athletes receive full scholarships or, more commonly, a partial scholarship or none at all. But regardless of whether an athlete draws 50,000 paying fans to the stadium or plays for an audience of several hundred, his or her max “compensation” is the same: a scholarship.

Student-Athletes

The term student-athlete sounds like it was invented by a particularly talented disciple of Plato who competed in the Olympics, but the phrase has a sordid history.

The NCAA invented the term as college sports gained prominence in the 1950s as a way to describe the status of young students competing in a very commercial industry. Its first use was to make sure that courts did not grant legal protections like worker’s compensation to college athletes. Author and historian Taylor Branch describes the birth of the term:

“The term came into play in the 1950s, when the widow of Ray Dennison, who had died from a head injury received while playing football in Colorado for the Fort Lewis A&M Aggies, filed for workmen’s-compensation death benefits. Did his football scholarship make the fatal collision a ‘work-related’ accident? Was he a school employee, like his peers who worked part-time as teaching assistants and bookstore cashiers? Or was he a fluke victim of extracurricular pursuits?

“…The Colorado Supreme Court ultimately agreed with the school’s contention that he was not eligible for benefits, since the college was ‘not in the football business.’”

Since the fifties, corporate logos have been plastered on athletes’ jerseys and the fact that colleges are in the football business seems clear. Nevertheless, Branch notes that the “student-athlete defense” continues to defeat liability cases in court. Universities have no obligation to cover all the costs of athletes’ medical care. An upset mother testified before Congress in 2011 that she received a $10,000 bill for an MRI performed on her injured son after a basketball game. Players that develop chronic injuries playing college sports often receive nothing from schools once their careers end. They are left to wallow in debt as they try to pay medical bills and overcome their handicaps.

Lack of medical coverage is just one example of the hypocrisy resulting from a billion dollar industry sitting on top of a supposedly amateur sports league. Another is that a profitable activity that would get a player suspended is business as usual for athletic departments. Branch notes this in the case of a player selling a jersey:

“At the start of the 2010 football season, A. J. Green, a wide receiver at Georgia, confessed that he’d sold his own jersey from the Independence Bowl the year before, to raise cash for a spring-break vacation. The NCAA sentenced Green to a four-game suspension for violating his amateur status with the illicit profit generated by selling the shirt off his own back. While he served the suspension, the Georgia Bulldogs store continued legally selling replicas of Green’s No. 8 jersey for $39.95 and up.”

College athletes also have no right to profit off their own likeness, even as the NCAA does so. Media giant Electronic Arts pays the NCAA to use the names of its teams, bowl games, and whatnot in video games like NCAA Football and NCAA Basketball. It also pays the NFL to produce the Madden series – video games based on the NFL. In the case of Madden, Electronic Arts pays over $35 million in royalties to the NFL players union for using players’ names and images. The only difference between Madden and NCAA Football is that the college version does not include names, yet the NCAA did not share any money with the players.

The NCAA waves away these inconsistencies by pointing to athletes’ amateur status and arguing that student-athletes receive the most valuable benefit of all: a college education. But waiving tuition and providing an education can be two distinct things.

Athletic time commitments are so high that only very productive individuals get the full benefit of their tuition. That is particularly true for the many basketball and football players who come from disadvantaged backgrounds and need more time to catch up with the skills of their peers. The time requirements of elite college athletics are 50 plus hours a week, not including travel time. The NCAA and athletic conferences also frequently schedule games during exam periods and playoffs into the following semesters.

Further, the practice of universities shepherding athletes toward easy classes and even minimizing academic obligations through fake classes and academic fraud seems systemic. Articles on scandals of this sort occur frequently. There are no good statistics or sources investigating whether it is systemic because the NCAA – the protectors of the student-athlete ideal – allow athletic departments to self-report students’ grades and only investigate when accusations of fraud are made public. But the one public metric the NCAA requires to maintain academic standards is revealing: their Academic Progress Rate requires that a mere 50% of teams’ players be on track to graduate.

There are student-athletes in football and basketball that excel academically and value the discipline, teamwork, and enjoyment of their athletic commitments as a valuable complement to their time in college. There are also students who are eager to shirk their academic obligations.

But given that an education is the justification of college sports, the NCAA and many college programs are cavalier about seeing athletes get one. A 1973 NCAA rule, for example, bans all but one year scholarship offers for athletes. Instead of offering 4 years guaranteed, universities must decide whether to renew every year. As a result, it is not uncommon for new coaches to take away an athlete’s scholarship in order to recruit a new prospect or to drop a scholarship belonging to a player who gets a career-ending injury.

In a trial over academic fraud, football powerhouse Georgia University explained how they still helped football players who did not receive the same level of education as other Georgia students:

“We may not make a university student out of him, but if we can teach him to read and write, maybe he can work at the post office rather than as a garbage man when he gets through with his athletic career.”

College athletes are not going completely unpaid. The scandal of athletes being paid under the table has been national news since 1929, when a report found that “Of the 112 schools surveyed, 81 flouted NCAA recommendations with inducements to students ranging from open payrolls and disguised booster funds to no-show jobs at movie studios.” Today’s strengthened NCAA does much to fight the system of college boosters and unscrupulous agents giving money to athletes, threatening athletes with suspensions if caught.

When these scandals come to light, it’s easy to see athletes in the wrong. Often they take money to fund parties or make frivolous purchases. But that does not take away from the exploitive nature of college sports culture.

Critics point out that athletes’ “full scholarships” provide $3,222 less per year than the real cost of their education and leave 85% of student-athletes living under the federal poverty line. And it is the NCAA that maintains a system that profits commercially off students while actively prioritizing a full-time commitment to sports over education.

Put another way, why does the NCAA target full compliance with the amateur idea of not being paid, but only a 50% graduation rate?

Where Does the Money Go?

A college degree can be a priceless opportunity. But it does have a price tag, and it is far below the value contributed by players at elite football and basketball schools.

The National College Player’s Association (NCPA), an advocacy organization, finds that the NCAA’s amateurism policy amounts to a “$6 billion heist.” While the average athletic scholarship at these schools is worth $23,204 per year, the NCPA finds that football and basketball players would command salaries of $137,357 and $289,031 respectively. As a result, over a 4 year college athletic career, football players at an elite program lose out on $456,612 and a men’s basketball player $1,063,307.

So where does that money go? According to sports economist Andrew Zimbalist, much of that money goes to the coach:

“In a normal marketplace, when you hire a worker, you pay the employee what they’re worth to you in a competitive circumstance. In this marketplace, you’re not allowed to pay the employee, right? So how do you recruit players? Presumably it has to do with the coach’s personality, the coach’s reputation, how well the coach is able to come on to the player and the parents of the player and so on and so forth.

So it’s not money that brings the player; it’s the coach: his reputation, his charisma, his charm… And so in that system, the coach ends up getting paid the money that would otherwise go to the player.”

One piece of evidence Zimbalist offers is to compare college coaches’ salaries to their professional counterparts. Since professional teams in the National Football League have revenues in the hundreds of millions and college football teams in the tens of millions, you would expect professional coaches to make much more. But they don’t. The best paid coaches in the National Football League make $5-$7 million. The highest paid college football coaches make $3-$5 million, plus perks like free use of private planes, cars, and country clubs.

If we take a college football coach at an elite athletic program to be overpaid by $2 million, that represents $23,529 of value taken from each player and given to the coach. In basketball, where teams have only 10-20 players, that number is over $100,000.

In some cases, the profits of college football and basketball teams subsidize non revenue generating sports. Teams don’t operate as silos; their financing all falls under the discretion of a single athletic director. As a result, a successful football team may generate $10 million of profit that subsidizes other sports like track and field and swimming. Of course, if athletes were paid, that profit would be lower. But as we’ll see, cases of profitable teams subsidizing other sports or otherwise returning money to the university are rare.

So where is the rest of the missing money? It’s likely padding the salaries and bottom lines of everyone profiting off college athletics: the assistant coaches, NCAA administrators (the president of the NCAA makes a cool $1.6 million per year), television companies, marketing companies, and so on.

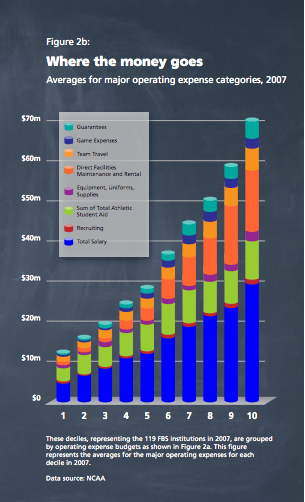

We can only conjecture that private companies receive more favorable terms due to college players not getting wages (it does make good economic sense), but we can see in the figure below how a bloated and/or overpaid staff takes up that surplus money. In the NFL, teams spend roughly 60% of their budgets on player salaries. As we see below, the biggest teams spend only 15% to 20% on scholarships. But they do spend 35% to 40% of their budget on staff salaries.

Source: Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics Primer

The Commercialized Nonprofit Frankenstein

Seventy-eight percent of Americans believe that college athletic departments are profitable. Given the ever increasing salaries of coaches, price tags of facilities, and national exposure, the belief is understandable. But this common perception of lucrative football and basketball programs covering the costs of entire athletic departments is a myth. No one knows this better than the colleges themselves. University presidents overwhelmingly view the high cost of athletics as a problem and athletic directors are busy cutting their budgets – a process only accelerated by the recession. Just over half of elite football and basketball programs turn a profit. Only 14 out of 120 athletic departments in the upper tier of Division I cover their costs. The remainder run a median deficit of $10 million.

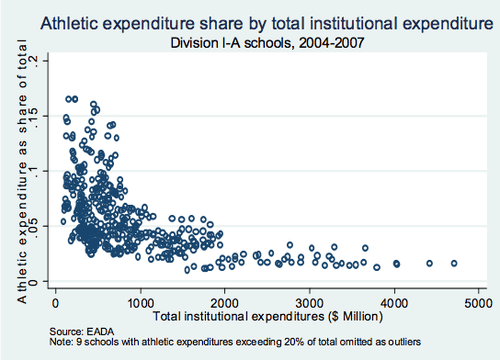

One could respond calmly that college athletic departments are not in the business of making money. Who cares if they operate at a loss? No one expects Division III athletics, or high school athletics for that matter, to make money. No one demands that the history department be shut down because it loses money each year. (Well, almost no one.) Colleges’ athletic expenditures represent only 6% on average of their annual budget. Athletics are a part of university life – isn’t it natural that it cost some money to run them?

However, there are a number of reasons to be critical of the deficits run by college athletic departments. College athletics’ blending of academic institutions with commercialism is at the heart of each.

The first is that deficits appear to be growing unsustainably. Economist Andrew Zimbalist estimates that if costs increase as they have over the past ten years, median yearly deficits will increase to $44 million in 2020.

One of the biggest factors behind this increase in prices is an “arms race” between elite teams. Professional football and basketball leagues have only 32 and 30 teams each, yet the highest division of college sports has 120 teams. There are far too many teams trying to be elite. In their competition over windfalls from March Madness appearances and BCS bowl games, universities spend large sums of money, gambling that a better coach, stadium, or marketing campaign can deliver them to the top of the pack. A report from the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics sums up the problems facing a team in a small sports market:

“Iowa State University of the Big 12 is an example of a have-not school in a big-time conference. It brings in a respectable $17 million per year in football revenue. Among its competitors are Texas, with $73 million in football revenue, and Nebraska, with $49 million in football revenue. But Iowa State’s fans and boosters expect its program to retain coaches and build facilities at the same level as their richer Big 12 colleagues. Keeping up with the Joneses is increasingly difficult, if not impossible.”

This arms race is enabled by the fact that college coaches are chasing commercial success in a nonprofit institution. The professionals running college athletics, particularly the coaches that hop between gigs at universities and in professional leagues, are hired to win. The incentives are to spend, spend, spend, not to achieve a level of success commensurate with the school’s market size, or to return a surplus to support the school’s academic mission. Coaches and college administrators simultaneously justify their high salaries and expensive facilities by pointing to the commercial nature of the league, and are shielded from their failure to turn a profit by the institutions’ nonprofit status and subsidies from the general budget.

The frankenstein marriage of big business and academic institutions also leads to runaway spending on sports that don’t generate income. To live up to its rhetoric about supporting the athletic experience for all students, rather than just those in profitable sports, the NCAA requires the highest level of Division I schools to field at least 15 division one teams. In the spirit of equality, schools feel pressure to spend large amounts of money on these other, non-revenue generating sports that could otherwise operate more like club sports, or at least be run more modestly.

Similarly, colleges’ commitment to gender equity – even if it is often half hearted – results in big expenditures on women’s sports. Complying with Title IX legislation, which bans sex-based discrimination at institutions receiving federal funding, is codified into NCAA rules. Schools do not need to spend equally on men and women’s sports, but they do need to facilitate equal opportunity to play. This mean, in particular, an equal number of athletic scholarships. As a result, even if providing 85 athletic scholarships reflects only the necessary spending to compete at a commercialized, elite level, that means that 85 scholarships still need to be found for women in non revenue generating sports.

Although not codified NCAA policy, the rhetorical commitment to gender equity of public institutions also puts upward pressure on the salaries of coaches of female sports. Although their sports don’t bring in revenue, they point to the salaries of their colleagues in men’s basketball and football in salary negotiations to demand similar paychecks.

While gender equity and the support of a diverse array of sports is admirable, it may be problematically that they take a commercialized sport as a benchmark. If a few sports were not so commercialized, couldn’t these other sports function more like club sports as they do overseas?

Another reason to scrutinize athletic departments’ deficits is that since the majority of the big athletic powers are public universities, and even private institutions enjoy nonprofit status, taxpayers are essentially footing the bill for the large and growing costs of college sports. In this light, costs are also incredibly understated. The largest source of athletic departments’ revenues is donations and contributions from alumni, often through “booster clubs” that support a specific sport. Like any donation, these contributions are tax-exempt, meaning that the government misses out on getting that money. Tax-exempt donations to support part of the college experience is a traditional part of how colleges operate, but is it justifiable to support elite athletic programs that make millions of dollars for coaches, select administrators, and executives of clothing brands and media companies?

There’s also the question of how the presence of a highly-commercialized, high revenue industry on campus affects college life. Football and basketball coaches are the most highly compensated public official in almost every state, with salaries typically 5 to 10 times higher than those of the university president. Since the recession, journalists have reported frequently on the phenomenon of professors being laid off and research budgets cut while coaches receive record salaries and bulldozers break ground on new stadiums. It is a cliché that college students don’t care about academics, and that they just care about beer, partying, and football. But how much more do universities need to prioritize sports over academics before it becomes university policy?

Too Big To Fail

In 1984, hometown hero Doug Flutie launched a hail mary pass as the last seconds ticked away in the Orange Bowl. His receiver improbably caught the pass in the endzone. The last minute throw became a staple of highlight reels and the game considered a classic. Flutie went on to win college football’s highest award, the Heisman Trophy.

Commentators like to say that this put Flutie’s school, Boston College, on the map. Among college administrators aware of the financial losses incurred by athletic departments, the spending is often justified as necessary to experience their own “Flutie effect”: achieving a level of nationwide recognition through sports that inspires bigger donations from alumni, better applicants, and a superior student body.

Research studies on these claims, however, find that these positive effects of athletic success are nonexistent or negligible. Summaries of the research in a Knight Commission report find that there is no meaningful correlation between athletic success and higher SAT scores of applicants, that the number of applicants may increase 2% to 8% after nationally publicized victories, but only for a short period, and that bowl game appearances seem to lead to modestly bigger donations, but often for the athletic department rather than financial aid or academics.

Instead, it seems that college administrators see the deficits and culture of college sports as a problem, but cannot tackle it. A survey of university presidents at schools with elite athletic programs found:

“Presidents would like serious change but don’t see themselves as the force for the changes needed, nor have they identified an alternative force they believe could be effective.”

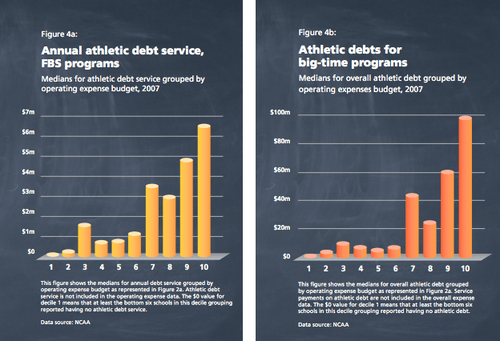

The scale of elite athletics programs has made them simply too big to fail. Debt payments and spending on new facilities is a large expense for schools – as much as 20% of athletic spending. Any wholesale attempt at reform, especially a move to an amateur model of sports, would face the barrier of ongoing expenses and multi-million dollar, long term deals with private companies for selling merchandise, broadcasting rights, and employee salaries. Locked into these big expenses, universities can only hope to succeed wildly and become one of the few programs with a profitable or sustainable athletic budget. But most are trying to dig themselves out of a whole.

Source: Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics Primer

The other barrier to change is the sheer popularity of college athletics and power of school pride. The animal spirits that bristle in defense of elite athletic programs are strong. One university president describes how presidents all know that taking on the athletic department is the best way to an early retirement:

“The presidents who have had their heads handed to them? A high percentage of them had that happen because it was something to do with athletics.”

Board members, alumni benefactors, and even state politicians want to see their school win big on the national stage. When university presidents try to restore athletics to a subordinate role in an academic institution, they find themselves pressured or removed by the university’s most important supporters. Presidents’ number one job is fundraising, and no one feels they can fundraise when they undercut the chances of the school’s popular sports teams.

In 2011, the president of Penn State fired Joe Paterno, the longtime and very successful coach of the football team. Paterno had failed to act on knowledge that one of his assistant coaches was sexually assaulting children, at one point in campus facilities. In response, Penn State students rioted. When facing such deep-seated emotions, what chance do brainy college presidents have?

Conclusion

The majority of college athletes are able to enjoy the student-athlete ideal. Competing is a choice, and can be a valuable complement to their college education. Among the elite programs, however, the introduction of corporate sponsors and huge television deals has benefitted many coaches, administrators, and other college athletes, but not necessarily the football and basketball players themselves. Instead, they find themselves performing a full-time job without the benefits and protections of employment, and all too often as students in name only.

Despite the huge revenues of elite college sports, athletic departments are losing money. By combining the risks and costs of a commercial enterprise with the subsidies and goals of a nonprofit institution, universities face runaway costs. The biggest expense is the arms race between schools to outspend each other on coaches and facilities in the hope of winning championships and becoming one of the few schools with an athletic department that balances its budget.

When they fail, however, everyone pays. As public institutions, the subsidies pouring into college sports are student fees and taxpayer dollars. That spending also challenges the academic culture of universities, as academics face budget cuts while athletics lavishes money on coaches and facilities. College presidents and a number of reformers recognize the problem, but don’t see how to solve it. Between long term television contracts and large debt payments on new stadiums, the rat race over college sports’ spoils is simply too big to fail. Those presidents that do take on the college sports juggernaut find themselves looking for a new job. They are no match for the passion that college sports can inspire in fans, alumni, board members, and political officials in defense of their beloved teams.

With the foolish passion of an injured player returning to the field or of rioting fans burning cars to defend their school’s pride, college athletics looks set to keep rushing forward on its destructive path.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. For a comprehensive critique of college sports, see Taylor Branch’s article in The Atlantic. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.